Guantanamo Bay detention camp

| Location | Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 19°54′03″N 75°05′59″W / 19.90083°N 75.09972°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Population | 15 (as of January 2025) |

| Opened | January 11, 2002 |

| Managed by | United States Navy |

The Guantanamo Bay detention camp,[note 1] also known as GTMO (/ˈɡɪtmoʊ/ GIT-moh), GITMO (/ˈɡɪtmoʊ/ GIT-moh), or simply Guantanamo Bay, is a United States military prison within Naval Station Guantanamo Bay (NSGB), on the coast of Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. It was established in January 2002 by U.S. President George W. Bush to hold terrorism suspects and "illegal enemy combatants" during the Global War on Terrorism following the attacks of September 11, 2001. As of January 2025, at least 780 people from 48 countries have been detained at the camp since its creation, of whom 756 had been transferred elsewhere, 9 died in custody, and 15 remain.[1]

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, the U.S. declared its "war on terror" effort and led a multinational military operation against Taliban-ruled Afghanistan to dismantle Al-Qaeda and capture its leader, Osama bin Laden. During the invasion, on November 13, 2001, President Bush issued a military order allowing for the indefinite detention of foreign nationals without charge and preventing them from legally challenging their detention. The following month, the U.S. Department of Justice claimed that habeas corpus—a legal recourse against unlawful detention—did not apply to Guantanamo Bay because it was outside of U.S. territory. Subsequently, in January 2002, a temporary detention facility dubbed "Camp X-Ray" was created to house suspected Al-Qaeda members and Taliban fighters primarily captured in Afghanistan.[2]

By May 2003, the Guantanamo Bay detention camp had grown into a larger and more permanent facility that housed over 680 prisoners, the vast majority without formal charges.[3][2][4] The Bush Administration maintained that it was not obliged to grant prisoners basic protections under the U.S. Constitution or the Geneva Conventions, since the former did not extend to foreign soil and the latter did not apply to "unlawful enemy combatants". Various humanitarian and legal advocacy groups claimed that these policies were unconstitutional and violated international human rights law;[5][6] several landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions found that detainees had rights to due process and habeas corpus but were still subject to military tribunals, which remain controversial for allegedly lacking impartiality, independence, and judicial efficiency.[7][8]

In addition to restrictions on their legal rights, detainees are widely reported to have been housed in unfit conditions and routinely abused and tortured, often in the form of "enhanced interrogation techniques".[9][10] As early as October 2003, the International Committee of the Red Cross warned of "deterioration in the psychological health of a large number of detainees".[11] Subsequent reports by international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as intergovernmental institutions such as the Organization of American States and the United Nations, concluded that detainees have been systematically mistreated in violation of their human rights.[11][12]

Amid multiple legal and political challenges, as well as consistent widespread criticism and condemnation both domestically and internationally, the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay has been subject to repeated calls and efforts for closure. President Bush, while maintaining that the facility was necessary and that prisoners were treated well, nonetheless expressed his desire to have it closed in the beginning of 2005.[13] His administration began winding down the detainee population in large numbers, ultimately releasing or transferring around 540.[2] In 2009, Bush's successor, Barack Obama, issued executive orders to close the facility within one year and identify lawful alternatives for its detainees; however, strong bipartisan opposition from the U.S. Congress, on the grounds of national security, prevented its closure.[14] During the Obama Administration, the number of inmates was reduced from about 250 to 41, but controversial policies such as the use of military courts were left in place.[15][16] In January 2018, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to keep the detention camp open indefinitely,[17] and only one prisoner was repatriated during his administration.[18] Since taking office in 2021, President Joe Biden has vowed to close the camp before his term ends,[19][20] although his administration has continued with multimillion-dollar expansions to military courtrooms and other Guantanamo Bay facilities.[21][22][23]

Following the release of 25 detainees from Guantanamo by January 2025,[24][25][26][27] 15 detainees remain as of January 2025;[28] of these, 3 are awaiting transfer, 9 have been charged or convicted of war crimes, and three are held in indefinite law-of-war detention without facing tribunal charges nor being recommended for release.[1]

History

[edit]

During the 1898 Spanish–American War, U.S. forces invaded and occupied Cuba amid its war of independence against Spain. In 1901, an American-drafted amendment to the Cuban constitution nominally recognized Cuba's sovereignty while allowing the U.S. to intervene in local affairs and establish naval bases on land leased or purchased from the Cuban government. The Cuban–American Treaty of Relations of 1903 reaffirmed these provisions, and that same year, the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base was established pursuant to a lease agreement with no expiration date. The 1934 Cuban–American Treaty of Relations superseded much of the 1903 treaty but reaffirmed the Guantánamo Bay lease, under which Cuba retains ultimate sovereignty but the U.S. exercises sole jurisdiction. Since coming to power in 1959, Cuba's communist government considers the U.S. military presence at Guantánamo Bay illegal and has repeatedly called for its return.[29]

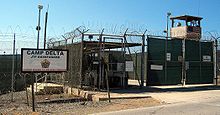

The Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, including the detention camp, is operated by the Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) of the Southern Command of the Department of Defense (DoD).[30] The main detention compound is Camp Delta, which replaced the temporary Camp X-Ray in April 2002, with other compounds including Camp Echo, Camp Iguana, and the Guantanamo psychiatric ward.[31]

After political appointees at the U.S. Office of Legal Counsel, Department of Justice advised the George W. Bush administration that "a federal district court could not properly exercise habeas jurisdiction over an alien detained at GBC (Guantanamo Bay, Cuba)",[32] military guards took the first twenty detainees to Camp X-Ray on January 11, 2002. At the time, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said the detention camp was established to detain extraordinarily dangerous people, to interrogate detainees in an optimal setting, and to prosecute detainees for war crimes.[33] In practice, the site has long been used for alleged "enemy combatants".

The DoD at first kept secret the identity of the individuals held in Guantanamo, but after losing attempts to defy a Freedom of Information Act request from the Associated Press, the U.S. military officially acknowledged holding 779 prisoners in the camp.[34]

The Bush administration asserted that detainees were not entitled to any of the protections of the Geneva Conventions, while also claiming it was treating "all detainees consistently with the principles of the Geneva Convention."[33] Ensuing U.S. Supreme Court decisions since 2004 have determined otherwise and that U.S. courts do have jurisdiction: it ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld on June 29, 2006, that detainees were entitled to the minimal protections listed under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.[35] Following this, on July 7, 2006, the Department of Defense issued an internal memo stating that detainees would, in the future, be entitled to protection under Common Article 3.[36][37]

Current and former detainees have reported abuse and torture, which the Bush administration denied. In a 2005 Amnesty International report, the facility was called the "Gulag of our times."[38] In 2006, the United Nations unsuccessfully demanded that Guantanamo Bay detention camp be closed.[39] On 13 January 2009, Susan J. Crawford, appointed by Bush to review DoD practices used at Guantanamo Bay and oversee the military trials, became the first Bush administration official to concede that torture occurred at Guantanamo Bay on one detainee (Mohammed al-Qahtani), saying "We tortured Qahtani."[40]

On January 22, 2009, President Obama issued a request to suspend proceedings at Guantanamo military commission for 120 days and to shut down the detention facility that year.[41][42] On January 29, 2009, a military judge at Guantanamo rejected the White House request in the case of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, creating an unexpected challenge for the administration as it reviewed how the United States brings Guantanamo detainees to trial.[43] On May 20, 2009, the United States Senate passed an amendment to the Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2009 (H.R. 2346) by a 90–6 vote to block funds needed for the transfer or release of prisoners held at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[44] President Obama issued a presidential memorandum dated 15 December 2009, ordering Thomson Correctional Center, Thomson, Illinois to be prepared to accept transferred Guantanamo prisoners.[45]

The Final Report of the Guantanamo Review Task Force, dated January 22, 2010, published the results for the 240 detainees subject to the review: 36 were the subject of active cases or investigations; 30 detainees from Yemen were designated for "conditional detention" due to the poor security environment in Yemen; 126 detainees were approved for transfer; 48 detainees were determined "too dangerous to transfer but not feasible for prosecution".[46]

On January 6, 2011, President Obama signed the 2011 Defense Authorization Bill, which, in part, placed restrictions on the transfer of Guantanamo prisoners to the mainland or to foreign countries, thus impeding the closure of the facility.[47] In February 2011, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said that Guantanamo Bay was unlikely to be closed, due to opposition in the Congress.[48] Congress particularly opposed moving prisoners to facilities in the United States for detention or trial.[48] In April 2011, WikiLeaks began publishing 779 secret files relating to prisoners in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[49]

On November 4, 2015, President Barack Obama stated that he was preparing to unveil a plan to close the facility and move some of the terrorism suspects held there to U.S. soil. The plan would propose one or more prisons from a working list that includes facilities in Kansas, Colorado and South Carolina. Two others that were on the list, in California and Washington State, do not appear to have made the preliminary cut, according to a senior administration official familiar with the proposal.[50] By the end of the Obama Administration on January 19, 2017, however, the detention center remained open, with 41 detainees remaining.[15]

In June 2022, The New York Times publicly released photographs of the first camp detainees following a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.[51]

Post-Bush statements

[edit]In 2010, Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, a former aide to Secretary of State Colin Powell, stated in an affidavit that top U.S. officials, including President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, had known that the majority of the detainees initially sent to Guantánamo were innocent, but that the detainees had been kept there for reasons of political expedience.[52][53] Wilkerson's statement was submitted in connection with a lawsuit filed in federal district court by former detainee Adel Hassan Hamad against the United States government and several individual officials.[54] This supported numerous claims made by former detainees such as Moazzam Begg, a British citizen who had been held for three years in detention camps in Afghanistan and Guantanamo as an enemy combatant, under the claim that he was an al-Qaeda member who recruited for, and provided money for, al-Qaeda training camps and himself trained there to fight US or allied troops.[55]

Camp facilities

[edit]

Camp Delta was a 612-unit detention center finished in April 2002. It included detention camps 1 through 4, as well as Camp Echo, where detainees not facing military commissions are held.[56]

Camp X-Ray was a temporary detention facility, which was closed in April 2002. Its prisoners were transferred to Camp Delta.

In 2008, the Associated Press reported Camp 7, a separate facility on the naval base that was considered the highest security jail on the base.[57] That facility held detainees previously imprisoned in a global, clandestine network of CIA prisons.[58] An attorney first visited a detainee at Camp 7 in 2013.[59] The precise location of Camp 7 has never been confirmed. In early April 2021, Camp 7 was shut down due to deteriorating conditions of the facilities.[60][61] The remaining prisoners at Camp 7 were transferred to Camp 5.[62]

Camp 5, as well as Camp 6, were built in 2003–04. They are modeled after a high-security facility in Indiana.[63] In September 2016, Camp 5 was closed and a portion of it dedicated to use as a medical facility for detainees.[64] A portion of Camp 5 was again re-dedicated in early April 2021, when Camp 7 so-called "high value" former CIA detainees were moved there.[65] In Camp 6, the U.S. government detains those who are not convicted in military commissions.[citation needed]

In January 2010, Scott Horton published an article in Harper's Magazine describing "Camp No", a black site about 1 mile (1.6 km) outside the main camp perimeter, which included an interrogation center. His description was based on accounts by four guards who had served at Guantanamo. They said prisoners were taken one at a time to the camp, where they were believed to be interrogated. He believes that the three detainees that DoD announced as having committed suicide were questioned under torture the night of their deaths.

From 2003 to 2006, the CIA operated a small site, known informally as "Penny Lane," to house prisoners whom the agency attempted to recruit as spies against Al-Qaeda. The housing at Penny Lane was less sparse by the standards of Guantanamo Bay, with private kitchens, showers, televisions, and beds with mattresses. The camp was divided into eight units. Its existence was revealed to the Associated Press in 2013.[66]

Camp conditions and testimonies of abuse and torture

[edit]A 2013 Institute on Medicine as a Profession (IMAP) report concluded that health professionals working with the military and intelligence services "designed and participated in cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment and torture of detainees." Medical professionals were ordered to ignore ethical standards during involvement in abusive interrogation, including monitoring of vital signs under stress-inducing procedures. They used medical information for interrogation purposes and participated in force-feeding of hunger strikers, in violation of World Medical Association and American Medical Association prohibitions.[67]

Supporters of controversial techniques have declared that certain protections of the Third Geneva Convention do not apply to Al-Qaeda or Taliban fighters, claiming that the Convention applies to only military personnel and guerrillas who are part of a chain of command, wear distinctive insignia, bear arms openly, and abide by the rules of war. Jim Phillips of The Heritage Foundation said that "some of these terrorists who are not recognized as soldiers don't deserve to be treated as soldiers."[68] Critics of U.S. policy, such as George Monbiot, claimed the government had violated the Conventions in attempting to create a distinction between "prisoners of war" and "illegal combatants."[69][70] Amnesty International called the situation "a human rights scandal" in a series of reports.[71]

One of the allegations of abuse at the camp is the abuse of the religion of the detainees.[72][73][74][75][76][77] Prisoners released from the camp have alleged incidents of abuse of religion including flushing the Quran down the toilet, defacing the Quran, writing comments and remarks on the Quran, tearing pages out of the Quran, and denying detainees a copy of the Quran. One of the justifications offered for the continued detention of Mesut Sen, during his Administrative Review Board hearing, was:[78]

Emerging as a leader, the detainee has been leading the detainees around him in prayer. The detainees listen to him speak and follow his actions during prayer.

Red Cross inspectors and released detainees have alleged acts of torture,[79][80] including sleep deprivation, beatings and locking in confined and cold cells.

The use of Guantánamo Bay as a military prison has drawn criticism from human rights organizations and others, who cite reports that detainees have been tortured[81] or otherwise poorly treated. Supporters of the detention argue that trial review of detentions has never been afforded to prisoners of war, and that it is reasonable for enemy combatants to be detained until the cessation of hostilities.

Testimonies of treatment

[edit]Three British Muslim prisoners, known in the media at the time as the "Tipton Three", were repatriated to the United Kingdom in March 2004, where officials immediately released them without charge. The three alleged ongoing torture, sexual degradation, forced drugging, and religious persecution being committed by U.S. forces at Guantánamo Bay.[82][83] The former Guantanamo detainee Mehdi Ghezali was freed without charge on 9 July 2004, after two and a half years internment. Ghezali claimed that he was the victim of repeated torture. Omar Deghayes alleged he was blinded after his right eye was gouged by an officer.[84] Juma Al Dossary claimed he was interrogated hundreds of times, beaten, tortured with broken glass, barbed wire, burning cigarettes, and suffered sexual assaults.[85] David Hicks also made allegations of torture[86][87] and mistreatment in Guantanamo Bay, including sensory deprivation, stress positions,[88] having his head slammed into concrete, repeated anal penetration, routine sleep deprivation[86] and forced drug injections.[89]

An Associated Press report claimed that some detainees were turned over to the U.S. by Afghan tribesmen in return for cash bounties.[90] The first Denbeaux study, published by Seton Hall University Law School, reproduced copies of several leaflets, flyers, and posters the U.S. government distributed to advertise the bounty program; some of which offered bounties of "millions of dollars."[91]

Hunger-striking detainees claimed that guards were force feeding them in the fall of 2005: "Detainees said large feeding tubes were forcibly shoved up their noses and down into their stomachs, with guards using the same tubes from one patient to another. The detainees say no sedatives were provided during these procedures, which they allege took place in front of U.S. physicians, including the head of the prison hospital.[92][93] "A hunger striking detainee at Guantánamo Bay wants a judge to order the removal of his feeding tube so he can be allowed to die", one of his lawyers has said.[94] Within a few weeks, the Department of Defense "extended an invitation to United Nations Special Rapporteurs to visit detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay Naval Station."[95][96] This was rejected by the U.N. because of DoD restrictions, stating that "[the] three human rights officials invited to Guantánamo Bay wouldn't be allowed to conduct private interviews" with prisoners.[97] Simultaneously, media reports began related to the question of prisoner treatment.[98] District Court Judge Gladys Kessler also ordered the U.S. government to release medical records going back a week before such feedings took place.[99] In early November 2005, the U.S. suddenly accelerated, for unknown reasons, the rate of prisoner release, but this was not sustained.[100] Detainee Mansur Ahmad Saad al-Dayfi has alleged that during his time as a JAG officer in Guantanamo, Ron DeSantis oversaw force-feedings of detainees.[101][102][103]

In May 2013, detainees undertook a widespread hunger strike; they were subsequently being force fed until the U.S. Government stopped releasing hunger strike information, due to it having "no operational purpose".[104] During the month of Ramadan that year, the US military claimed that the amount of detainees on hunger strike had dropped from 106 to 81. However, according to defense attorney Clive Stafford Smith, "The military are cheating on the numbers as usual. Some detainees are taking a token amount of food as part of the traditional breaking of the fast at the end of each day in Ramadan, so that is now conveniently allowing them to be counted as not striking."[105] In 2014, the Obama administration undertook a "rebranding effort" by referring to the hunger strikes as "long term non-religious fasting."[106]

Attorney Alka Pradhan petitioned a military judge to order the release of art made in her client, Ammar al-Baluchi's cell. She complained that painting and drawing was made difficult, and he was not permitted to give artwork to his counsel.[107]

It has been reported that prisoners cooperating with interrogations have been rewarded with Happy Meals from the McDonald's on base.[108]

Reported suicides

[edit]By May 2011, there had been at least six reported suicides in Guantánamo.[109][110]

During August 2003, there were 23 suicide attempts. The U.S. officials did not say why they had not previously reported the incident.[111] After this event, the Pentagon reclassified alleged suicide attempts as "manipulative self-injurious behaviors". Camp physicians alleged that detainees do not genuinely wish to end their lives, rather, the prisoners supposedly feel that they may be able to get better treatment or release with suicide attempts. Daryl Matthews, a professor of forensic psychiatry at the University of Hawaii who examined the prisoners, stated that given the cultural differences between interrogators and prisoners, "intent" was difficult if not impossible to ascertain. Clinical depression is common in Guantánamo, with 1/5 of all prisoners being prescribed antidepressants such as Prozac.[112] Guantanamo Bay officials have reported 41 suicide attempts by 25 detainees since the U.S. began taking prisoners to the base in January 2002.[113] Defense lawyers contend the number of suicide attempts is higher.[113]

On 10 June 2006 three detainees were found dead, who, according to the DoD, "killed themselves in an apparent suicide pact."[114] Prison commander Rear Admiral Harry Harris claimed this was not an act of desperation, despite prisoners' pleas to the contrary, but rather "an act of asymmetric warfare committed against us."[113][115] The three detainees were said to have hanged themselves with nooses made of sheets and clothes. According to military officials, the suicides were coordinated acts of protests.

Human rights activists and defense attorneys said the deaths signaled the desperation of many of the detainees. Barbara Olshansky of the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represented about 300 Guantánamo detainees, said that detainees "have this incredible level of despair that they will never get justice." At the time, human rights groups called for an independent public inquiry into the deaths.[116] Amnesty International said the apparent suicides "are the tragic results of years of arbitrary and indefinite detention" and called the prison "an indictment" of the George W. Bush administration's human rights record.[113] Saudi Arabia's state-sponsored Saudi Human Rights group blamed the U.S. for the deaths. "There are no independent monitors at the detention camp so it is easy to pin the crime on the prisoners... it's possible they were tortured," said Mufleh al-Qahtani, the group's deputy director, in a statement to the local Al-Riyadh newspaper.[113]

Highly disturbed about the deaths of its citizens under U.S. custody, the Saudi government pressed the United States to release its citizens into its custody. From June 2006 through 2007, the U.S. released 93 detainees (of an original 133 Saudis detained) to the Saudi Arabian government. The Saudi government developed a re-integration program including religious education, helping to arrange marriages and jobs, to bring detainees back into society.[117]

The Center for Policy and Research published Death in Camp Delta (2009), its analysis of the NCIS report, noting many inconsistencies in the government account and said the conclusion of suicide by hanging in their cells was not supported.[118][119] It suggested that camp administration officials had either been grossly negligent or were participating in a cover-up of the deaths.[120]

In January 2010 Scott Horton published an article in Harper's Magazine disputing the government's findings and suggesting the three died of accidental manslaughter following torture. His account was based on the testimony of four members of the Military Intelligence unit assigned to guard Camp Delta, including a decorated non-commissioned Army officer who was on duty as sergeant of the guard the night of 9–10 June 2006. Their account contradicts the report published by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). Horton said the deaths had occurred at a black site, known as "Camp No", outside the perimeter of the camp.[121][122][123][124][125] According to its spokeswoman Laura Sweeney, the Department of Justice has disputed certain facts contained in the article about the soldiers' account.[116]

Torture

[edit]The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) inspected some of the prison facilities in June 2004. In a confidential report issued in July 2004 and leaked to the New York Times in November 2004, Red Cross inspectors accused the U.S. military of using "humiliating acts, solitary confinement, temperature extremes, and use of forced positions" against prisoners. The inspectors concluded that "the construction of such a system, whose stated purpose is the production of intelligence, cannot be considered other than an intentional system of cruel, unusual and degrading treatment and a form of torture." The United States government reportedly rejected the Red Cross findings at the time.[126][127][128]

On 30 November 2004, the New York Times published excerpts from an internal memo leaked from the U.S. administration,[126] referring to a report from the ICRC. The ICRC reports of several activities that, it said, were "tantamount to torture": exposure to loud noise or music, prolonged extreme temperatures, or beatings. It also reported that a Behavioral Science Consultation Team (BSCT), also called 'Biscuit,' and military physicians communicated confidential medical information to the interrogation teams (weaknesses, phobias, etc.), resulting in the prisoners losing confidence in their medical care.

The ICRC's access to the base was conditioned, as is normal for ICRC humanitarian operations, on the confidentiality of their report. Following leaking of the U.S. memo, some in the ICRC wanted to make their report public or confront the U.S. administration. The newspaper said the administration and the Pentagon had seen the ICRC report in July 2004 but rejected its findings.[129][127] The story was originally reported in several newspapers, including The Guardian,[130] and the ICRC reacted to the article when the report was leaked in May.[128]

According to a 21 June 2005 New York Times opinion article,[131] on 29 July 2004, an FBI agent was quoted as saying, "On a couple of occasions, I entered interview rooms to find a detainee chained hand and foot in a fetal position to the floor, with no chair, food or water. Most times, they had urinated or defecated on themselves and had been left there for 18, 24 hours or more." Air Force Lt. Gen. Randall Schmidt, who headed the probe into FBI accounts of abuse of Guantánamo prisoners by Defense Department personnel, concluded the man (Mohammed al-Qahtani, a Saudi, described as the "20th hijacker") was subjected to "abusive and degrading treatment" by "the cumulative effect of creative, persistent and lengthy interrogations."[132] The techniques used were authorized by the Pentagon, he said.[132]

Many of the released prisoners have complained of enduring beatings, sleep deprivation, prolonged constraint in uncomfortable positions, prolonged hooding, cultural and sexual humiliation, enemas[133] as well as other forced injections, and other physical and psychological mistreatment during their detention in Camp Delta.

During the Mubarak era, it's been alleged that Egyptian State Security officers and agents travelled to Cuba and tortured detainees. They also allegedly trained U.S. soldiers on torture techniques.

In 2004, Army Specialist Sean Baker, a soldier posing as a prisoner during training exercises at the camp, was beaten so severely that he suffered a brain injury and seizures.[134] In June 2004, The New York Times reported that of the nearly 600 detainees, not more than two dozen were closely linked to al-Qaeda and that only very limited information could have been received from questionings. In 2006, the only top terrorist was reportedly Mohammed al Qahtani from Saudi Arabia, who is believed to have planned to participate in the September 11 attacks in 2001.[135]

Mohammed al-Qahtani was refused entry at Orlando International Airport, which stopped him from his plan to take part in the 9/11 attacks. During his Guantánamo interrogations, he was given 3+1⁄2 bags of intravenous fluid, and then forbidden to use the toilet, forcing him to soil himself. Accounts of the type of treatment he received include: having water poured over him, interrogations starting at midnight and lasting 12 hours, psychological torture methods such as sleep deprivation via repeatedly being woken up by loud, raucous music whenever he would fall asleep, and military dogs being used to intimidate him. Soldiers would play the American national anthem and force him to salute, he had images of victims of the September 11 attacks affixed to his body, he was forced to bark like a dog, and his beard and hair were shaved, an insult to Muslim men. He would be humiliated and upset by female personnel, was forced to wear a bra, and was stripped nude and had fake menstrual blood smeared on him, while being made to believe it was real. Some of the abuses were documented in 2005, when the Interrogation Log of al-Qathani "Detainee 063" was partially published.[136][137][138]

The Washington Post, in an 8 May 2004 article, described a set of interrogation techniques approved for use in interrogating alleged terrorists at Guantánamo Bay. Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, characterized them as cruel and inhumane treatment illegal under the U.S. Constitution.[139] On 15 June, Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, commander at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq during the prisoner abuse scandal, said she was told from the top to treat detainees like dogs "as it is done in Guantánamo [Camp Delta]." The former commander of Camp X-Ray, Geoffrey Miller, had led the inquiry into the alleged abuses at Abu Ghraib during the Allied occupation. Ex-detainees of the Guantanamo Camp have made serious allegations, including alleging Geoffrey Miller's complicity in abuse at Camp X-Ray.

In "Whose God Rules?" David McColgin, a defense attorney for Guantanamo detainees, recounts how a female government interrogator told Muslim detainees she was menstruating, "slipped her hand into her pants and pulled it out with a red liquid smeared on it meant to look like menstrual blood. The detainee screamed at the top of his lungs, began shaking, sobbing, and yanked his arms against his handcuffs. The interrogator explained to [the detainee] that he would now feel too dirty to pray and that she would have the guards turn off the water in his cell so he would not be able to wash the red substance off. 'What do you think your brothers will think of you in the morning when they see an American woman's menstrual blood on your face?' she said as she left the cell." These acts, as well as interrogators desecrating the Quran, led the detainees to riots and mass suicide attempts.[138][140]

The BBC published a leaked FBI email from December 2003, which said that the Defense Department interrogators at Guantánamo had impersonated FBI agents while using "torture techniques" on a detainee.[141]

In an interview with CNN's Wolf Blitzer in June 2005, Vice President Dick Cheney defended the treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo:

There isn't any other nation in the world that would treat people who were determined to kill Americans the way we're treating these people. They're living in the tropics. They're well fed. They've got everything they could possibly want.[142]

The United States government, through the State Department, makes Periodic Reports to the United Nations Committee Against Torture as part of its treaty obligations under the U.N. Convention Against Torture. In October 2005, the U.S. report covered pretrial detention of suspects in the "War on Terrorism", including those held in Guantánamo Bay. This Periodic Report is significant as the first official response of the U.S. government to allegations that prisoners are mistreated in Guantánamo Bay. While the 2005 report denies allegations of "serious abuse," it does detail 10 "substantiated incidents of misconduct," and the training and punishments given to the perpetrators.[143]

Writing in the New York Times on 24 June 2012, former President Jimmy Carter criticized the methods used to obtain confessions: "Some of the few being tried (only in military courts) have been tortured by waterboarding more than 100 times or intimidated with semiautomatic weapons, power drills or threats to sexually assault their mothers. These facts cannot be used as a defense by the accused, because the government claims they occurred under the cover of 'national security'".[144]

Sexual abuse

[edit]In 2005, it was reported that sexual methods were allegedly used by interrogators to break Muslim prisoners.[145] In a 2015 article from The Guardian, it was claimed that the CIA used sexual abuse along with a wider array of other forms of torture. Detainee Majid Khan testified that interrogators "poured ice water on his genitals, twice videotaped him naked and repeatedly touched his private parts", according to the same article.[146]

Operating procedures

[edit]

A manual called "Camp Delta Standard Operating Procedure" (SOP), dated 28 February 2003, and designated "Unclassified//For Official Use Only", was published on WikiLeaks. This is the main document for the operation of Guantánamo Bay, including the securing and treatment of detainees. The 238-page document includes procedures for identity cards and 'Muslim burial'. It is signed by Major General Geoffrey D. Miller. The document is the subject of an ongoing legal action by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which has been trying to obtain it from the Department of Defense.[147][148]

On 2 July 2008, the New York Times revealed that the U.S. military trainers who came to Guantánamo Bay in December 2002 had based an interrogation class on a chart copied directly from a 1957 Air Force study of Chinese Communist interrogation methodology (subsequently referred to as "brainwashing") that the United States alleged were used during the Korean War to obtain confessions. The chart showed the effects of "coercive management techniques" for possible use on prisoners, including "sleep deprivation", "prolonged constraint" (also known as "stress positions") and "exposure". The chart was copied from a 1957 article (entitled "Communist Attempts to Elicit False Confessions From Air Force Prisoners of War") written by Albert D. Biderman, a sociologist working for the Air Force. Biderman had interviewed American prisoners of war returning from Korea who had confessed to having taken part in biological warfare or involvement in other atrocities. His article sets out that the most common interrogation method used by the Chinese was to indirectly subject a prisoner to extended periods of what would initially be minor discomfort. As an example, prisoners would be required to stand for extended periods, sometimes in a cold environment. Prolonged standing and exposure to cold are an accepted technique used by the American military and the CIA to interrogate prisoners whom the United States classifies as "unlawful combatants" (spies and saboteurs in wartime; "terrorists" in unconventional conflicts) although it is classified as torture under the Geneva Conventions. The chart reflects an "extreme model" created by Biderman to help in "understanding what occurred apart from the extent to which it was realized in actuality". His chart sets out in summary bullet points the techniques allegedly used by the Chinese in Korea, the most extreme of which include "Semi-Starvation", "Exploitation of Wounds", and use of "Filthy, Infested Surroundings" to make the prisoner "Dependent on Interrogator", to weaken "Mental and Physical Ability to Resist", and to reduce the "Prisoner to 'Animal Level'".[149]

It should be understood that only a few of the Air Force personnel who encountered efforts to elicit false confessions in Korea were subjected to really full dress, all-out attempts to make them behave in the manner I have sketched. The time between capture and repatriation for many was too short, and, presumably, the trained interrogators available to the Communists too few, to permit this. Of the few Air Force prisoners who did get the full treatment, none could be made to behave in complete accordance with the Chinese Communists' ideal of the "repentant criminal".[150]

The article was motivated by the need for the United States to deal with prominent confessions of war crimes obtained by Chinese interrogators during the Korean War. The report led the American military to develop a training program to counter the use of such methods used by an enemy interrogator. Almost all U.S. military personnel now receive Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) training to resist interrogation. Central to this training program are the interrogation methods presented by Biderman. In 2002, this training program was adopted as a source of interrogation techniques to be used in the newly declared "War on Terror".[149] When it was adopted for use at the Guantánamo detention and interrogation facility the only change that was made to Biderman's Chart was to change the title (originally called "Communist Coercive Methods for Eliciting Individual Compliance"). The training document was made public at a United States Senate Armed Services Committee hearing (17 June 2008) investigating how such tactics came to be employed. Col. Steven Kleinman, who was head of a team of SERE trainers, testified that his team had been put under pressure to demonstrate the techniques on Iraqi prisoners and that they had been sent home after Kleinman had observed that the techniques were intended to be used as a "form of punishment for those who wouldn't cooperate", and put a stop to it.[151] Sen. Carl Levin (chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee) was quoted after reviewing the evidence as saying:

What makes this document doubly stunning is that these were techniques to get false confessions. People say we need intelligence, and we do. But we don't need false intelligence.[152][153]

Camp detainees

[edit]Since January 2002, 779 men have been brought to Guantanamo.[154][155] Nearly 200 were released by mid-2004, before there had been any CSRTs (Combatant Status Review Tribunal) to review whether individuals were rightfully held as enemy combatants.[clarification needed][109] Of all detainees at Guantanamo, Afghans were the largest group (29 percent), followed by Saudi Arabians (17 percent), Yemenis (15 percent), Pakistanis (9 percent), and Algerians (3 percent). Overall, 50 nationalities were present at Guantanamo.[156]

Although the Bush administration said most of the men had been captured fighting in Afghanistan, a 2006 report prepared by the Center for Policy and Research at Seton Hall University Law School reviewed DoD data for the remaining 517 men in 2005 and "established that over 80% of the prisoners were captured not by Americans on the battlefield but by Pakistanis and Afghans, often in exchange for bounty payments."[120] The U.S. widely distributed leaflets in the region and offered $5,000 per prisoner. One example is Adel Noori, a Chinese Uyghur and dissident who had been sold to the US by Pakistani bounty hunters.[157]

Top DoD officials often referred to these prisoners as the "worst of the worst", but a 2003 memo by then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said "We need to stop populating Guantanamo Bay (GTMO) with low-level enemy combatants... GTMO needs to serve as an [redacted] not a prison for Afghanistan."[158] The Center for Policy and Research's 2006 report, based on DoD released data, found that most detainees were low-level offenders who were not affiliated with organizations on U.S. terrorist lists.

Eight men have died in the prison camp; DoD has said that six were suicides. DoD reported three men, two Saudis and a Yemeni, had committed suicide on 10 June 2006. Government accounts, including an NCIS report released with redactions in August 2008, have been questioned by the press, the detainees' families, the Saudi government, former detainees, and human rights groups.[citation needed]

An estimated 17 to 22 minors under the age of 18 were detained at Guantánamo Bay, and it has been claimed that this is in violation of international law. According to Chaplain Kent Svendsen who served as chaplain for the detention centers from 2004 to 2005 there were no minor detainees at the site upon starting his assignment in early 2004. He said: "I was given a tour of the camp and it was explained to me that minors were segregated from the general public and processed to be returned to their families. The camp had long been emptied and closed when I arrived at my duty station".[159][160]

In July 2005, 242 detainees were moved out of Guantanamo, including 173 who were released without charge. Sixty-nine prisoners were transferred to the custody of governments of other countries, according to the DoD.[161]

The Center for Constitutional Rights has prepared biographies of some of the prisoners currently being held in Guantanamo Prison.[162]

By May 2011, 600 detainees had been released.[109] Most of the men were released without charges or transferred to facilities in their home countries. According to former U.S. president Jimmy Carter, about half were cleared for release, yet had little prospect of ever obtaining their freedom.[144]

As of June 2013, 46 detainees (in addition to two who were deceased) were designated to be detained indefinitely, because the government said the prisoners were too dangerous to transfer and there was insufficient admissible evidence to try them.[163]

After the release of Saifullah Paracha in October 2022, 35 prisoners remained, 20 of which had been cleared for release, pending identification of a suitable country.[164]

As of 20 April 2023, 30 detainees remained at Guantanamo Bay.[165]

The fates of former detainees after their release from Guantanamo are mixed. Many have attempted to reintegrate into normal life in their home countries. Some have sought and won refugee status away from their home country, such as Maasoum Abdah Mouhammad and Ahmed Abdul Qader. Some re-engaged in "terror-related activities" since their release, such as Ibrahim al Qosi. Others were incarcerated in their home countries after having been returned, such as Yunis Abdurrahman Shokuri and Aziz Abdul Naji.[166]

High-value prisoners

[edit]In September 2006, President Bush announced that 14 "high-value detainees" were to be transferred to military custody of the Guantánamo Bay detention camp from civilian custody by the CIA. He admitted that these suspects had been held in CIA secret prisons overseas, known as black sites. These people include Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, believed to be the No. 3 Al-Qaeda leader before he was captured in Pakistan in 2003; Ramzi bin al-Shibh, an alleged would-be 9/11 hijacker; and Abu Zubaydah, who was believed to be a link between Osama bin Laden and many Al-Qaeda cells, who were captured in Pakistan in March 2002.[167]

In 2011, human rights groups and journalists found that some of these prisoners had been taken to other locations, including in Europe, and interrogated under torture in the U.S. extraordinary rendition program before arriving at Guantanamo.[168][169]

On 11 February 2008, the U.S. military charged Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi, Ali Abd Al-Aziz Ali and Walid bin Attash with committing the September 11 attacks, under the military commission system, as established under the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA).[170] In Boumediene v. Bush (2008), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the MCA was unconstitutional.

On 5 February 2009, charges against Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri were dropped without prejudice after an order by Obama to suspend trials for 120 days.[171] Abd Al-Rahim Al-Nashiri was accused of renting a small boat connected with the USS Cole bombing.

On 31 July 2024, Mohammed, Attash, & al-Hawsawi all agreed to plead guilty to avoid the death penalty. In exchange, they will be given life sentences and be transferred from Guantanamo Bay to ADX Florence.[172][173] The plea deal was revoked by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin two days later.[174][175] The pleas deals have since been reinstated, since the defense secretary did not have the required authority to revoke them and furthermore acted too late according to a military judge. [176] Once the three inmates are transferred, this will reduce the remaining number of detainees to 27, slowly edging towards closing the base.

Government and military inquiries

[edit]

Senior law enforcement agents with the Criminal Investigation Task Force told msnbc.com in 2006 that they began to complain inside the Defense Department in 2002 that the interrogation tactics used by a separate team of intelligence investigators were unproductive, not likely to produce reliable information and probably illegal. Unable to get satisfaction from the Army commanders running the detainee camp, they took their concerns to David Brant, director of the NCIS, who alerted Navy General Counsel Alberto J. Mora.[177]

General Counsel Mora and Navy Judge Advocate General Michael Lohr believed the detainee treatment to be unlawful and campaigned among other top lawyers and officials in the Defense Department to investigate, and to provide clear standards prohibiting coercive interrogation tactics.[178]

In response, on 15 January 2003, Donald Rumsfeld suspended the approved interrogation tactics at Guantánamo until a new set of guidelines could be produced by a working group headed by General Counsel of the Air Force Mary Walker. The working group based its new guidelines on a legal memo from the Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel written by John Yoo and signed by Jay S. Bybee, which would later become widely known as the "Torture Memo."[179]

General Counsel Mora led a faction of the Working Group in arguing against these standards, and argued the issues with Yoo in person. The working group's final report, was signed and delivered to Guantánamo without the knowledge of Mora and the others who had opposed its content. Nonetheless, Mora has maintained that detainee treatment has been consistent with the law since 15 January 2003 suspension of previously approved interrogation tactics.[179]

On 1 May 2005, the New York Times reported on a high-level military investigation into accusations of detainee abuse at Guantánamo, conducted by Lt. Gen. Randall M. Schmidt of the Air Force, and dealing with:

accounts by agents for the Federal Bureau of Investigation who complained after witnessing detainees subjected to several forms of harsh treatment. The F.B.I. agents wrote in memorandums that were never meant to be disclosed publicly that they had seen female interrogators forcibly squeeze male prisoners' genitals, and that they had witnessed other detainees stripped and shackled low to the floor for many hours.[180][181]

In June 2005, the United States House Committee on Armed Services visited the camp and described it as a "resort" and complimented the quality of the food. Democratic members of the committee complained that Republicans had blocked the testimony of attorneys representing the prisoners.[182] On 12 July 2005, members of a military panel told the committee that they proposed disciplining prison commander Army Major General Geoffrey Miller over the interrogation of Mohamed al-Kahtani, who was regularly beaten, humiliated, and psychologically assaulted. They said the recommendation was overruled by General Bantz J. Craddock, commander of U.S. Southern Command, who referred the matter to the Army's inspector general.[citation needed]

The Senate Armed Services Committee Report on Detainee Treatment was declassified and released in 2009. It stated,

The abuse of detainees in U.S. custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of "a few bad apples" acting on their own. The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees. Those efforts damaged our ability to collect accurate intelligence that could save lives, strengthened the hand of our enemies, and compromised our moral authority.[183]

Legal issues

[edit]President Bush's military order

[edit]On 14 September 2001, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, giving the President of the United States broad powers to prosecute a War on Terror in response to the September 11 attacks.[184] Secretary of State Colin Powell and State Department Legal Advisor William Howard Taft IV advised that the President must observe the Geneva Conventions.[185] Colonel Lawrence Morris proposed holding public hearings modeled on the Nuremberg trials.[186] Major General Thomas Romig, the Judge Advocate General of the United States Army, recommended any new military tribunals be modeled on existing courts-martial.[185]

However, Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel Jay Bybee, relying on the unitary executive theory developed by Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo, advised the president in a series of memos that he could hold enemy combatants abroad, indefinitely, without congressional oversight, and free from judicial review.[185] On 13 November 2001, President George W. Bush signed a military order titled the Detention, Treatment, and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism, which sought to detain and try enemy combatants by military commissions under presidential authority alone.[185]

Rasul v. Bush (2004)

[edit]On 19 February 2002, Guantanamo detainees petitioned in federal court for a writ of habeas corpus to review the legality of their detention. U.S. District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly denied the detainees' petitions on 30 July 2002, finding that aliens in Cuba had no access to U.S. courts.[187]

In Al Odah v. United States, a panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit including Judge Merrick Garland affirmed on 11 March 2003.[188]

On 28 June 2004, the Supreme Court of the United States decided against the Government in Rasul v. Bush.[189] Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for a five-justice majority, held that the detainees had a statutory right to petition federal courts for habeas review.[190]

That same day, the Supreme Court ruled against the Government in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.[191] Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote the four-justice plurality opinion finding that an American citizen detained in Guantanamo had a constitutional right to petition federal courts for habeas review under the Due Process Clause.[190]

Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006)

[edit]Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz responded by creating "Combatant Status Review Tribunals" (CSRTs) to determine if detainees were unlawful combatants.[192][193] Detainees' habeas petitions to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia were consolidated into two cases.[194] In one, Judge Richard J. Leon rejected the detainees' petition because they "have no cognizable Constitutional rights" on 19 January 2005.[195] In the other, Judge Joyce Hens Green granted the detainees' petition, finding the CSRTs violated the detainees' constitutional rights on 31 January 2005.[196] Separately, on 8 November 2004, Judge James Robertson had granted Salim Hamdan's petition challenging that the military commission trying the detainee for war crimes was not a competent tribunal, prompting commentary by European law professors.[197][198]

The Combatant Status Reviews were completed in March 2005. Thirty-eight of the detainees were found not to be enemy combatants. After the dossier of determined enemy combatant Murat Kurnaz was accidentally declassified Judge Green wrote it "fails to provide significant details to support its conclusory allegations, does not reveal the sources for its information and is contradicted by other evidence in the record."[199] Eugene R. Fidell, said that, the Kurnaz' dossier, "suggests the [CSRT] procedure is a sham; if a case like that can get through, then the merest scintilla of evidence against someone would carry the day for the government, even if there's a mountain of evidence on the other side."[199]

The Washington Post included the following cases as among those showing the problems with the CSRT process: Mustafa Ait Idir, Moazzam Begg, Murat Kurnaz, Feroz Abbasi, and Martin Mubanga.[200][199]

On 15 July 2005, a panel of the D.C. Circuit including then-Circuit Judge John Roberts vacated all those lower rulings and threw out the detainees' petitions.[201] On 7 November 2005, the Supreme Court agreed to review that judgment. On 30 December 2005, Congress responded by passing the Detainee Treatment Act, which changed the statute to explicitly strip detainees of any right to petition courts for habeas review.[185]

On 29 June 2006, the Supreme Court decided against the Government in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld.[202] Justice Stevens, writing for a five-justice majority, found that courts had jurisdiction to hear those detainees' petitions which had been filed before Congress enacted the DTA and that the CSRTs violated the Geneva Conventions standards enacted in the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[203]

Boumediene v. Bush (2008)

[edit]Congress responded by passing the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which gave statutory authorization to the CSRTs and was explicit in retroactively stripping detainees of any right to petition courts for habeas review.[204] On 20 February 2007, D.C. Circuit Judge A. Raymond Randolph, joined by Judge David B. Sentelle upheld the Act and dismissed the detainees' petitions, over the dissent of Judge Judith W. Rogers.[205]

On 12 June 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court decided against the government in Boumediene v. Bush.[206] Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for a five-justice majority, held that the detainees had a right to petition federal courts for writs of habeas corpus under the United States Constitution.[184] Justice Antonin Scalia strongly dissented, writing that the Court's decision, "will almost certainly cause more Americans to be killed".[184]

Other court rulings

[edit]After being ordered to do so by U.S. District Judge Jed S. Rakoff, on 3 March 2006, the Department of Defense released the names of 317 out of approximately 500 alleged enemy combatants being held in Guantánamo Bay, citing again privacy concerns as reason to withhold some names.[207][208]

French judge Jean-Claude Kross, on 27 September 2006, postponed a verdict in the trial of six former Guantánamo Bay detainees accused of attending combat training at an al Qaeda camp in Afghanistan, saying the court needs more information on French intelligence missions to Guantánamo. Defense lawyers for the six men, all French nationals, accused the French government of colluding with U.S. authorities over their detentions; they said the government sought to use inadmissible evidence, as it was obtained through secret service interviews with the detainees without their lawyers present. Kross scheduled new hearings for 2 May 2007, calling the former head of counterterrorism at the French Direction de la surveillance du territoire intelligence agency to testify.[209]

On 21 October 2008, United States district court Judge Richard J. Leon ordered the release of the five Algerians held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and the continued detention of a sixth, Bensayah Belkacem.[210]

Access to counsel

[edit]In the summer of 2012, the government instituted a new protocol for civilian attorneys representing Guantanamo prisoners. It required lawyers to sign a memorandum of understanding, in which they agreed to certain restrictions, in order to continue to see their clients.[211] A federal court order had governed lawyers' access to their detainee clients and classified information related to their capture and confinement. Government lawyers sought court approval to replace the court's protective order with the MOU, to enable military officials to establish and enforce their own rules about when and how detainees could have access to legal counsel.[citation needed]

Under the rules of the MOU, lawyers' access was restricted for those detainees who no longer have legal challenges pending. The new government rules tightened access to classified information and gave the commander of the Joint Task Force Guantanamo complete discretion over lawyers' access to the detainees, including visits to the base and letters. The Justice Department took the position that Guantanamo Bay detainees whose legal challenges have been dismissed do not need the same level of access to counsel as detainees who are still fighting in court.[211]

On 6 September 2012, U.S. District Chief Judge Royce C. Lamberth rejected the government's arguments. Writing that the government was confusing "the roles of the jailer and the judiciary," Judge Lamberth rejected the military's assertion that it could veto meetings between lawyers and detainees.[212] Judge Lamberth ruled that access by lawyers to their detainee-clients at Guantánamo must continue under the terms of a long-standing protective order issued by federal judges in Washington.[211]

International law

[edit]In April 2004, Cuban diplomats tabled a United Nations resolution calling for a UN investigation of Guantánamo Bay.[213]

In May 2007, Martin Scheinin, a United Nations rapporteur on rights in countering terrorism, released a preliminary report for the United Nations Human Rights Council. The report stated the United States violated international law, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, that the Bush Administration could not try such prisoners as enemy combatants in a military tribunal and could not deny them access to the evidence used against them.[214] Prisoners have been labeled "illegal" or "unlawful enemy combatants," but several observers such as the Center for Constitutional Rights and Human Rights Watch maintain that the United States has not held the Article 5 tribunals required by the Geneva Conventions.[215] The International Committee of the Red Cross has stated that, "Every person in enemy hands must have some status under international law: he is either a prisoner of war and, as such, covered by the Third Convention, a civilian covered by the Fourth Convention, [or] a member of the medical personnel of the armed forces who is covered by the First Convention. There is no intermediate status; nobody in enemy hands can fall outside the law." Thus, if the detainees are not classified as prisoners of war, this would still grant them the rights of the Fourth Geneva Convention, as opposed to the more common Third Geneva Convention, which deals exclusively with prisoners of war. A U.S. court has rejected this argument as it applies to detainees from al Qaeda.[70] Henry T. King, Jr., a prosecutor for the Nuremberg Trials, has argued that the type of tribunals at Guantánamo Bay "violates the Nuremberg principles" and that they are against "the spirit of the Geneva Conventions of 1949."[216]

Some have argued in favor of a summary execution of all unlawful combatants, using Ex parte Quirin as the precedent, a case during World War II that upheld the use of military tribunals for eight German saboteurs caught on U.S. soil while wearing civilian clothes. The Germans were deemed to be unlawful combatants and thus not entitled to POW status. Six of the eight were executed as spies in the electric chair on the request of the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The validity of this case, as basis for denying prisoners in the War on Terrorism protection by the Geneva Conventions, has been disputed.[217][218][219] A report by the American Bar Association commenting on this case, states that the Quirin case "does not stand for the proposition that detainees may be held incommunicado and denied access to counsel." The report notes that the Quirin defendants could seek review and were represented by counsel.[220]

A report published in April 2011 in the PLoS Medicine journal looked at the cases of nine individuals for evidence of torture and ill treatment and documentation by medical personnel at the base by reviewing medical records and relevant legal case files (client affidavits, attorney–client notes and summaries, and legal affidavits of medical experts). The findings in these nine cases from the base indicate that medical doctors and mental health personnel assigned to the DoD neglected and/or concealed medical evidence of intentional harm, and the detainees complained of "abusive interrogation methods that are consistent with torture as defined by the UN Convention Against Torture as well as the more restrictive US definition of torture that was operational at the time".[221] The group Physicians for Human Rights has claimed that health professionals were active participants in the development and implementation of the interrogation sessions, and monitored prisoners to determine the effectiveness of the methods used, a possible violation of the Nuremberg Code, which bans human experimentation on prisoners.[222]

Lease agreement for Guantanamo

[edit]The base, which is considered legally to be leased by the Cuban government to the United States, is on territory that is recognized by both governments to be sovereign Cuban territory. The naval base at Guantanamo Bay was leased by Cuba to the American government through the "Agreement Between the United States and Cuba for the Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval stations", signed by the President of Cuba and the President of the United States on 23 February 1903. The lease agreement from 1903 says in Article 2:

The grant of the foregoing Article shall include the right to use and occupy the waters adjacent to said areas of land and water, and to improve and deepen the entrances thereto and the anchorages therein, and generally to do any and all things necessary to fit the premises for use as coaling or naval stations only, and for no other purpose.

— Agreement Between the United States and Cuba for the Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval stations; February 23, 1903[223]

In 1934, the newly revised Cuban–American Treaty of Relations reaffirmed Article 2's provision of the previous treaty of leasing Guantánamo Bay Naval Base to the United States. Article 3 of the treaty states:

Until the two contracting parties agree to the modification or abrogation of the stipulations of the agreement in regard to the lease to the United States of America of lands in Cuba for coaling and naval stations signed by the President of the Republic of Cuba on February 16, 1903, and by the President of the United States of America on the 23d day of the same month and year, the stipulations of that agreement with regard to the naval station of Guantanamo shall continue in effect. The supplementary agreement in regard to naval or coaling stations signed between the two Governments on July 2, 1903, also shall continue in effect in the same form and on the same conditions with respect to the naval station at Guantanamo. So long as the United States of America shall not abandon the said naval station of Guantanamo or the two Governments shall not agree to a modification of its present limits, the station shall continue to have the territorial area that it now has, with the limits that it has on the date of the signature of the present Treaty.

— Treaty Between the United States of America and Cuba; May 29, 1934[224]

The post-1959 Cuban government claimed the treaty was forced upon them by the United States and therefore was a not valid legal agreement. However, Article 4 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties says its provisions shall not be applied retroactively.

Guantanamo military commission

[edit]The American Bar Association announced that: "In response to the unprecedented attacks of September 11, on 13 November 2001, the President announced that certain non-citizens [of the US] would be subject to detention and trial by military authorities. The order provides that non-citizens whom the government deems to be, or to have been, members of the al Qaida organization or to have engaged in, aided or abetted, or conspired to commit acts of international terrorism that have caused, threaten to cause, or have as their aim to cause, injury to or adverse effects on the United States or its citizens, or to have knowingly harbored such individuals, are subject to detention by military authorities and trial before a military commission."[225]

On 28 and 29 September 2006, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, respectively, passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, a controversial bill that allows the President to designate certain people with the status of "unlawful enemy combatants" thus making them subject to military commissions, where they have fewer civil rights than in regular trials.

"Camp Justice"

[edit]

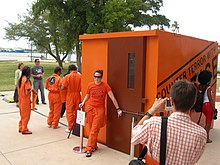

In 2007, Camp Justice was the informal name granted to the complex where Guantánamo detainees would face charges before the Guantanamo military commissions, as authorized by the Military Commissions Act of 2006. It was named by Sgt Neil Felver of the 122 Civil Engineering Squadron in a contest.[226][227][228] Initially the complex was to be a permanent facility, costing over $100 million. The U.S. Congress overruled the Bush Administration's plans. The camp was redesigned as a portable, temporary facility, costing approximately $10 million.

On 2 January 2008, the Toronto Star reporter Michelle Shephard offered an account of the security precautions that reporters go through before they can attend the hearings:[229]

- Reporters were not allowed to bring in more than one pen;

- Female reporters were frisked if they wore underwire bras;

- Reporters were not allowed to bring in their traditional coil-ring notepads;

- The bus bringing reporters to the hearing room is checked for explosives before it leaves;

- 200 meters from the hearing room, reporters dismount, pass through metal detectors, and are sniffed by chemical detectors for signs of exposure to explosives;

- Eight reporters are allowed into the hearing room—the remainder watch over closed circuit television.

Reporters are not supposed to hear the sound from the court directly. A 20-second delay is inserted. If a classified document is read, a red light starts and the sound is turned off immediately.[230]

On 1 November 2008, David McFadden of the Associated Press stated the 100 tents erected to hold lawyers, reporters and observers were practically deserted when he and two other reporters covered the military commission for Ali Hamza al-Bahlul in late October 2008.[231]

Three detainees have been convicted by military court of various charges:

- David Hicks, an Australian citizen, was found guilty in a plea bargain, of providing material support for terrorism in 2001, according to his military lawyer under retrospective legislation introduced in 2006.[232][233] On 18 February 2015, David Hicks' appeal against his conviction was upheld by the United States Military Commission Review and his conviction was overturned.[234]

- Salim Hamdan was convicted of being Osama bin Laden's driver.[235] After his release, he appealed his case. On 16 October 2012, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated Hamdan's conviction, on the grounds that the acts he was charged with under the Military Commissions Act of 2006 were not, in fact, crimes at the time he committed them, rendering it an ex post facto prosecution.[236]

Release of prisoners

[edit]Two hundred detainees were released in 2004 before any Combatant Status Review Tribunals were held, including the Tipton Three, all British citizens.

On 27 July 2004, four French detainees were repatriated and remanded in custody by the French intelligence agency Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire.[237] The remaining three French detainees were released in March 2005.[238]

On 4 August 2004, the Tipton Three, ex-detainees who had been returned to the UK in March of that year (and freed by the British authorities within 24 hours of their return) filed a report in the US claiming persistent severe abuse at the camp, of themselves and others.[239]

Administrative Review Board

[edit]The detainees at Guantanamo Bay prison underwent a series of CSRTs with the purpose of confirming or vacating their statuses as enemy combatants. In these reviews, the prisoners were interviewed thoroughly on the details of their crimes and roles in Taliban and al Qaeda activities, including the extent of their relationship and correspondence with Osama Bin Laden. In these interviews, the detainees also extensively detailed the alleged abuse and neglect that they faced while in detention at Guantanamo Bay Prison.[240] The events described by these prisoners violated the Geneva Conventions standards of conduct with prisoners of war, yet the conventions were previously claimed to not protect members of the Taliban or al Qaeda militias in correspondence between the department of defense and the assistant attorney general and U.S. department of justice in 2002.[241] The full versions of these Combatant Status Reviews were released in 2016 in response to an ACLU lawsuit.[242]

Besides convening CSRTs, the DoD initiated a similar, annual review. Like the CSRTs, the Board did not have a mandate to review whether detainees qualified for POW status under the Geneva Conventions. The Board's mandate was to consider the factors for and against the continued detention of detainees, and make a recommendation either for their retention, release, or transfer to the custody of their country of origin. The first set of annual reviews considered the dossiers of 463 detainees. The first board met between 14 December 2004, and 23 December 2005. The Board recommended the release of 14 detainees, and repatriation of 120 detainees to the custody of their country of origin.

By November 2005, 358 of the then-505 detainees held at Guantanamo Bay had Administrative Review Board hearings.[243] Of these, 3% were granted and were awaiting release, 20% were to be transferred, 37% were to be further detained at Guantanamo, and no decision had been made in 40% of the cases.

Of two dozen Uyghur detainees at Guantanamo Bay, The Washington Post reported on 25 August 2005, fifteen were found not to be "enemy combatants."[244] Although cleared of terrorism, these Uyghurs remained in detention at Guantanamo because the United States refused to return them to China, fearing that China would "imprison, persecute or torture them" because of internal political issues. US officials said that their overtures to approximately 20 countries to grant the individuals asylum had been declined, leaving the men with no destination for release.[244] On 5 May 2006, five Uyghurs were transported to refugee camps in Albania and the Department of Justice filed an "Emergency Motion to Dismiss as Moot" on the same day.[245] One of the Uyghurs' lawyers characterized the sudden transfer as an attempt "to avoid having to answer in court for keeping innocent men in jail."[246][247]

In August 2006, Murat Kurnaz, a legal resident of Germany, was released from Guantánamo with no charges after having been held for five years.[248]

President Obama

[edit]As of 15 June 2009, Guantánamo held more than 220 detainees.[249]

The United States was negotiating with Palau to accept a group of innocent Chinese Uyghur Muslims who have been held at the Guantánamo Bay.[250] The Department of Justice announced on 12 June 2009, that Saudi Arabia had accepted three Uyghurs.[249] The same week, one detainee was released to Iraq, and one to Chad.[249]

Also that week, four Uyghur detainees were resettled in Bermuda, where they were released.[249] On 11 June 2009, the US Government negotiated a deal in secret with the Bermudian Premier, Ewart Brown, to release four Uyghur detainees to Bermuda, an overseas territory of the UK. The detainees were flown into Bermuda under the cover of darkness. The US purposely kept the information of this transfer secret from the UK, which handles all foreign affairs and security issues for Bermuda, as it was feared that the deal would collapse. After the story was leaked by the US media, Premier Brown gave a national address to inform the people of Bermuda. Many Bermuda residents objected, as did the UK Government. It undertook an informal review of the actions; the Bermuda opposition, UBP, made a tabled vote of no confidence in Brown.

Italy agreed on 15 June 2009, to accept three prisoners.[249] Ireland agreed on 29 July 2009, to accept two prisoners. The same day, the European Union said that its member states would accept some detainees.[249] In January 2011, WikiLeaks revealed that Switzerland accepted several Guantanamo detainees as a quid pro quo with the U.S. to limit a multibillion tax probe against Swiss banking group UBS.[251]

In December 2009, the U.S. reported that, since 2002, more than 550 detainees had departed Guantánamo Bay for other destinations, including Albania, Algeria, Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, Bahrain, Belgium, Bermuda, Chad, Denmark, Egypt, France, Hungary, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Maldives, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Palau, Portugal, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Sudan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, Canada, and Yemen.

The Guantanamo Review Task Force issued a Final Report 22 January 2010,[252] but did not publicly release it until 28 May of that year.[253] The report recommended releasing 126 then-current detainees to their homes or to a third country, prosecuting 36 in either federal court or by a military commission, and holding 48 indefinitely under the laws of war.[254] In addition, 30 Yemenis were approved for release if security conditions in their home country improve.[253] Since the release of the report, over 60 detainees have been transferred to other countries, while two detainees have died in custody.[255]

In March 2011, President Obama issued Executive Order 13567, which created the Periodic Review Board.[256] Senior Civil Service officials from six agencies sit on the Board and consider detainee transfers.[256] Each member has a veto over any recommendation.[256]

Under the Obama administration, the Board examined 63 detainees, recommending 37 of those to be transferred.

Of the 693 total former detainees transferred out of Guantanamo, 30% are suspected or confirmed to have engaged in terrorist activity after transfer.[256] Of those detainees who were transferred out under Obama, 5.6% are confirmed and 6.8% are suspected of engaging in terrorist activity after transfer.[256]

President Biden

[edit]On 19 July 2021, The U.S. Department of State under the Biden Administration released Moroccan national Abdul Latif Nasir into the custody of his home country. Nasir was the first Guantanamo detainee released since 2016 and after his departure 39 detainees still remained imprisoned.[257] Nasir was originally cleared for release by the Obama Administration in 2016 but remained in custody initially due to bureaucratic delays and later due to President Trump's policy changes restricting Guantanamo prisoner releases.[258] A State Department spokesman stated, "The Biden Administration remains dedicated to a deliberate and thorough process focused on responsibly reducing the detainee population and ultimately closing of the Guantanamo facility."[257] Critics have contended that the Biden administration may not be prepared or able to fully close the prison on the basis that, "In order to close the prison, Biden would need to move all 39 detainees to other prisons or locations", and that there have not been enough concrete steps taken in order to ensure existing detainees are successfully relocated and the closing steps are carried out.[19]

Over the course of spring 2022, the American government released three more detainees; Mohammed al-Qahtani, Sufyian Barhoumi, and Asadullah Haroon Gul. In fall 2022, the government released Saifullah Paracha, the oldest prisoner.[259] In January 2025, 11 Yemeni prisoners were transfered to Oman.[260]

In January 2025, the United States transferred 11 Yemeni prisoners from Guantánamo Bay to a detention facility in Oman, citing the reduced occupancy at the Guantanamo Bay facility. The Omani government agreed to host the detainees as part of a broader international effort to further reduce the detainee population at Guantanamo.[261]

Subsequent actions of some released detainees