East Germanic languages

| East Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Oder-Vistula Germanic, Illevionic (uncommon) | |

| Geographic distribution | Varying depending on time (4th–18th centuries), currently all languages are extinct Until late 4th century: Central and Eastern Europe (as far as Crimea) late 4th–early 10th centuries: Much of southern, western, southeastern, and eastern Europe (as far as Crimea) and North Africa early 10th–late 18th centuries — disputed (cp. Crimean Gothic): Isolated areas in Eastern Europe (as far as Crimea) |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-5 | gme |

| Glottolog | east2805 |

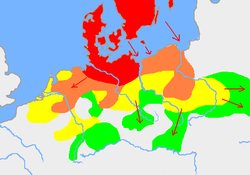

The distribution of the primary Germanic languages in Europe c. AD 1:

North Sea Germanic, or Ingvaeonic

Weser–Rhine Germanic, or Istvaeonic

Elbe Germanic, or Irminonic

East Germanic † | |

The East Germanic languages, also called the Oder-Vistula Germanic languages, are a group of extinct Germanic languages that were spoken by East Germanic peoples. East Germanic is one of the primary branches of Germanic languages, along with North Germanic and West Germanic.

The only East Germanic language of which texts are known is Gothic, although a word list and some short sentences survive from the debatedly-related Crimean Gothic. Other East Germanic languages include Vandalic and Burgundian, though the only remnants of these languages are in the form of isolated words and short phrases. Furthermore, the inclusion of Burgundian has been called into doubt.[1] Crimean Gothic is believed to have survived until the 18th century in isolated areas of Crimea.[2]: 189

History

[edit]

East Germanic was presumably native to the north of Central Europe, especially modern Poland, and likely even the first branch to split off from Proto-Germanic in the first millennium BC.

For many years, the least controversial theory of the origin of the Germanic (and East Germanic) languages was the so-called Gotho-Nordic hypothesis: that they originated in the Nordic Bronze Age of Southern Scandinavia and along the coast of the northernmost parts of Germany.[5]

By the 1st century AD, the writings of Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, and Tacitus indicate a division of Germanic-speaking peoples into large groupings with shared ancestry and culture. (This division has been taken over in modern terminology about the divisions of Germanic languages.)

Based on accounts by Jordanes, Procopius, Paul the Deacon and others, as well as linguistic, toponymic, and archaeological evidence, the East Germanic tribes, the speakers of the East Germanic languages related to the North Germanic tribes, had migrated from Scandinavia into the area lying east of the Elbe.[6] In fact, the Scandinavian influence on Pomerania and today's northern Poland from c. 1300–1100 BC (Nordic Bronze Age sub-period III) onwards was so considerable that this region is sometimes included in the Nordic Bronze Age culture.[7]

There is also archaeological and toponymic evidence which has been taken as suggesting that Burgundians lived on the Danish island of Bornholm (Old Norse: Burgundaholmr), and that Rugians lived on the Norwegian coast of Rogaland (Old Norse: Rygjafylki).[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]- East Germanic †[8][9][10][11]

- Gothic †

- Vandalic †

- Burgundian †

- Bastarnisch (German -isch corresponds to English -ish, -ic, -ian) †

- Gepidisch (Spoken by the Gepids) †

- Herulisch †

- Rugisch †

- Skirisch †

- Crimean Gothic † (disputed, alternatively considered to be West Germanic)[12]

Frederik Hartmann argues that East Germanic is not a valid genetic clade, as the three most attested languages conventionally identified as east Germanic (Burgundian, Vandalic, Gothic) do not share any common innovations with each other and all independently split from Proto-Germanic.[13] Hartmann instead prefers the term Eastern rim languages to refer to these languages. [14]

See also

[edit]- Ingvaeonic languages

- Irminonic languages

- Istvaeonic languages

- North Germanic languages

- West Germanic languages

- Balto-Slavic languages

References

[edit]- ^ Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0520085114.

For a long time linguists considered the Burgundians to be an East Germanic people, but today they are no longer so sure.

- ^ MacDonald Stearns Jr. (1989). "Das Krimgotische" [Crimean Gothic]. In Beck, Heinrich (ed.). Germanische Rest- und Trümmersprachen (in German). Berlin: W. de Gruyter. pp. 175–194. ISBN 3-11-011948-X.

- ^ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ^ John T. Koch (2020). "CELTO-GERMANIC, Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West", p. 38

- ^ The Penguin Atlas of World History, Hermann Kinder and Werner Hilgemann; translated by Ernest A. Menze; with maps designed by Harald and Ruth Bukor. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051054-0, 1988. Volume 1, p. 109.

- ^ Dabrowski 1989 p. 73

- ^ Heinz Mettke, Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, 8th ed., Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen, 2000, p. 16 (chart) and 17: „Hauptvertreter des Ostgermanischen ist das Gotische (Wulfilas Bibelübersetzung aus dem 4. Jh.), ferner gehören dazu das Burgundische, das Vandalische und das Rugische.“

- ^ Peter Ernst, Deutsche Sprachgeschichte, 3rd ed., 2021, p. 50: „Ostgermanisch (†): Gotisch, Vandalisch, Burgundisch, Rugisch, u.a. [= und andere]“

- ^ Harald Haarmann, Die Indoeuropäer: Herkunft, Sprachen, Kulturen, Verlag C.H.Beck, München, 2010, p. 71: „Ostgermanisch (ausgestorben): Gotisch, Gepidisch, Burgundisch, Vandalisch, Herulisch“

- ^ Georg F. Meier, Barbara Meier, Handbuch der Linguistik und Kommunikationswissenschaft: Band 1: Sprache, Sprachentstehung, Sprachen, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 1979, p. 73: „1.5.1.2. übrige ostgermanische Sprachen

Dazu gehören: Vandalisch, Herulisch, Rugisch, Gepidisch, Burgundisch, Bastarnisch und Skirisch. Diese Sprachen sind meist nur durch kurze Inschriften bzw. aus historischen Quellen bekannt.“ - ^ MacDonald Stearns, Das Krimgotische. In: Heinrich Beck (ed.), Germanische Rest- und Trümmersprachen, Berlin/New York 1989, p. 175–194, here the chapter Die Dialektzugehörigkeit des Krimgotischen on p. 181–185

- ^ Hartmann 2023, p. 187.

- ^ Hartmann 2023, p. 189.

Sources

[edit]- Dabrowski, J. (1989) Nordische Kreis und Kulturen Polnischer Gebiete. Die Bronzezeit im Ostseegebiet. Ein Rapport der Kgl. Schwedischen Akademie der Literatur, Geschichte und Altertumsforschung über das Julita-Symposium 1986. Ed Ambrosiani, Björn Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. Konferenser 22. Stockholm. ISBN 91-7402-203-2

- Demougeot, E. La formation de l'Europe et les invasions barbares, Paris: Editions Montaigne, 1969–74.

- Hartmann, Frederik / Riegger, Ciara. 2021. The Burgundian language and its phylogeny – A cladistical investigation. Nowele 75, p. 42-80.

- Kaliff, Anders. 2001. Gothic Connections. Contacts between eastern Scandinavia and the southern Baltic coast 1000 BCE – 500 CE.

- Musset, L. Les invasions: les vagues germanique, Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1965.

- Nordgren, I. 2004. Well Spring of The Goths. About the Gothic Peoples in the Nordic Countries and on the Continent.

- “Gothic Language.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 20 July 1998, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gothic-language.

- Hartmann, Frederik (2023). Germanic phylogeny. Oxford studies in diachronic and historical linguistics. Oxford, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-887273-3. OCLC 1347218384.